Memories of a European between Viennese Mitteleuropa and the Second World War

On the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the death of Stefan Zweig, Austrian writer, playwright, journalist, biographer (for fans of The Rose of Versailles, Ikeda-sensei also based on Marie Antoinette – The portait of an Avarage Woman by Zweig himself for the eponymous character), historian and poet, I decided to honor him with an article about his most important work: The World of Yesterday. I would like to thank the honourable professor of German History and Culture, Giovanna Neiger, immensely for making me discover this treasure.

Book cover of English edition, published by University of Nebraska (1st May 2013)

buy on

Book Depositary

Still und eng und ruhig auferzogen,

Wirft man uns auf einmal in die Welt;

Uns umspülen hunderttausend Wogen,

Alles reizt uns, mancherlei gefällt,

Mancherlei verdrießt uns, und von Stund zu Stunden

Schwankt das leichtunruhige Gefühl;

Wir empfinden, und was wir empfunden,

Spült hinweg das bunte Weltgewühl.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “An Lottchen”

Short biography

ATTENTION: THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH CONTAINS ELEMENTS THAT MAY OFFEND YOUR SENSIBILITIES. IF YOU ARE AN EASILY IMPRESSIONABLE PERSON, PLEASE HAPPILY SKIP THIS PARAGRAPH!

Stefan Zweig is for the first time in Brasil

The beginnings

Stefan Zweig was born in Vienna on 28 November 1881 into a prosperous Jewish family. He was the second son of two children of the industrialist Moritz Zweig (1845-1926) and Ida Brettauer (1854-1938), born in Ancona to a family from Hohenems, where they owned a bank. His youth was influenced by the family’s economic security and the artistic and intellectual climate of late 19th century Vienna. Like most of his peers, he took little interest in political and social problems. In 1900 he began his university studies at the Faculty of Philosophy, first in Vienna and then in Berlin from 1902 to 1904, the year of his graduation.

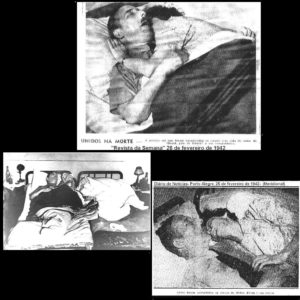

News of Mr and Mrs Zweig’s death in an English newspaper

Career

After his studies and with the support of his parents, he travelled around Europe and beyond, visiting the Asian and American continents, becoming friend of, for example, Lev Tolstoy, Rainer Maria Rilke, Benedetto Croce, James Joyce and Romain Rolland. He kept in touch and held secret meetings in Geneva and Zurich with these people during the First World War, which he absolutely refused to attend as a pacifist and cosmopolitan, and the first post-war period. In the meantime, he met and married Friderike Maria von Winternitz in 1920, who supported him to the end and helped him to write his memoir.

In 1933, Zweig’s works were burned by the Nazis. Zweig was proud to share this fate with Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and many others. In 1934 he left Austria for London without his family. After the annexation of his motherland by the Third Reich in 1938, he applied for and was granted British citizenship. In the same year he divorced Friderike and in 1939 married the young secretary Lotte (Charlotte) Altmann (1908-1942), with whom he moved to New York the following year, knowing well that he would never see Europe again.

Death

Images of their discovery published in a Brazilian newspaper, possibly local

In 1941 he moved to Petrópolis, Brazil, where he committed suicide with an overdose of barbiturates together with Lotte on 23 February 1942. Both were suffering from bouts of depression, partly due to exile and their lack of hope for the future of Europe, dominated by violence and authoritarianism. The bodies of Mr and Mrs Zweig are found dressed and composed on the bed, close together and as if peacefully asleep. Some incongruities initially make the Brazilian police think of the murder at the hands of sympathisers or secret agents of Nazi Germany, which considered him ‘the most dangerous Jewish intellectual’, but later the official version is accepted.

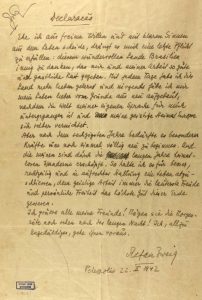

Original letter

Next to the bed is a farewell note, autographed and recognised as authentic, entitled Declaraçao (‘Declaration’ in Portuguese) which reads:

“I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on Earth. I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the

dawn after the long night!”

The memoir

By definition, a memoir is a biography or historical report, especially one based on personal knowledge. As can be deduced, the author may voluntarily omit information and this is what happens here. In fact, Zweig never mentions, for instance, the marriages he had. It is added that the memoir may contain distorted memories, but this is not the case.

In addition, Zweig has a goal with this writing, which he hopes to fulfil: he wants to speak to a future generation, far away from him and the situations of enormous change, about what he experienced in about 58 years of life (at least what he remembers), primarily by highlighting his testimony to the decline of moral and cultural values during his lifetime.

The work is divided into 16 chapters linked together and each with a different theme. There are 3 phases, called ‘lives’ by the author himself:

- Childhood and youth in Vienna

- World War I and the first post-war period around the world

- Exile in London, New York and Petrópolis

At the beginning, the work is very slow at the narrative level due to the author’s detailed but important descriptions, which help to reconstruct his vision and feelings at the precise moment he is narrating. However, after the general introduction he gives, the reading proceeds quickly and smoothly.

The writing began in 1934 and ended in 1942, shortly before his death. His ex-wife and the publisher received all the packets of papers with the author’s instructions for the publication of the book, which was published after his death.

Personal opinion

I think it absolutely must be read. It left me stunned and shocked, even with tears in my eyes towards the end of the reading, especially for the paragraph dedicated to Freud, Zweig’s great friend.

In my opinion, chapter 9 gets an honorable mention for a reason: the explanation of the difference between the two world wars and the key elements of each, such as the eagerness and over-romanticisation of war in the First. What struck me most is how many writers and poets of the time urged their readers to taking part on it using terms such as, for example, Krieg (war) rhyming with Sieg (victory) and Not (necessity) with Tod (death). I would also add the cutting off of German and Austrian writers’ relations with English or French writers only because of the war, as if they had never been friends with each other.

I end with the last lines of the work which also reflect our times:

The sun shone full and strong. Homeward bound I suddenly noticed before me my own shadow as I had seen the shadow of the other war behind the actual one. During all this time it has never budged from me, that irremovable shadow, it hovers over every thought of mine by day and by night; perhaps its dark outline lies on some pages of this book, too. But, after all, shadows themselves are born of light. And only he who has experienced dawn and dusk, war and peace, ascent and decline, only he has truly lived.