WandaVision is the first in a sequence of Marvel TV series – or rather, miniseries – since its acquisition by Disney.

It aired on Disney+ starting January 15th and recently ended after bringing to the streaming platform an original if not entirely well-landed story of grief and love.

Plot

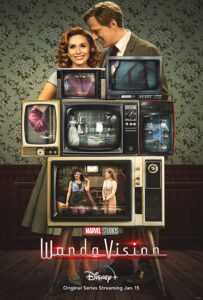

© Disney

Fluctuating between classic TV and the tried-and-tested Marvel Cinematic Universe formula, WandaVision brings to the screen a universe in which Wanda Maximoff and Vision have built a lovely little suburban life together, but not everything is what it seems in this small pocket of perfection.

Review

The first foray into television

With WandaVision, Disney ushers in a new phase of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and does so through a medium that isn’t entirely new for the comic book company but now follows a much different direction from the Marvel-related superhero shows we have seen so far.

As most of our readers certainly will remember, Wanda Maximoff (played by Elizabeth Olsen) and Vision (played by Paul Bettany) are not the first superheroes to get a TV adaptation or what passes for one when it comes to the new streaming mediums.

While both Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and Agent Carter predate the slew of Marvel TV shows coming from the hands of the collaboration with Netflix, it is much more interesting – and in some ways useful – to draw a confrontation between the new Disney+ shows and the now-cancelled Netflix adaptations.

Even considering that the new D+ shows are much more similar to the FOX shows in the way they link up to the greater cinematic universe, and therefore it would make a great amount of sense not to consider the Netflix series at all in this conversation, the setup for AoS and AC – not to forget Inhumans, Runaways, and Cloak & Dagger, plus others that went more or less forgotten and streamed only briefly on other platforms – has a much different approach to the serialisation of the stories, in my opinion.

But we’ll get back to that.

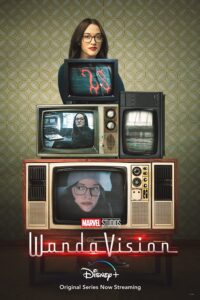

© Disney

WandaVision‘s… vision

WandaVision kicks off with a surprising and destabilising approach. Borrowing from the old classics of 1950 television and proceeding with the aesthetics and customs of the following several decades of sitcoms, it introduces us to Wanda and Vision’s couple life by presenting it like the perfect family structure that was dreamed up and deemed ideal in 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and finally contemporary sitcoms. We can immediately tell that something is not quite right, not just because no other Marvel story has ever employed such aestheticism, but also because the show makes a point of introducing subtle – but unsettling – displays of artificiality.

In this sense, WV makes capable use of nostalgic atmospheres of a type of television that we haven’t been familiar with for decades and that in some cases might be partly lost on foreign audiences that are not as knowledgeable about American pop culture as the average viewer from the U.S., while still transporting the story and fixing it into the context of what we have known so far of Marvel productions.

By the time the show arrives at more modern displays of sitcoms, the audience has had the time to acclimatise and can surely appreciate the weaving and the masterful unravelling in how the sitcom medium has evolved throughout the decades, while at the same time presenting a side-plot (which is actually the explanation and entire point of what’s been going on from the beginning) that contextualises it in the cinematic universe – and in the audience’s point of view even – and still enlarges it at the same time.

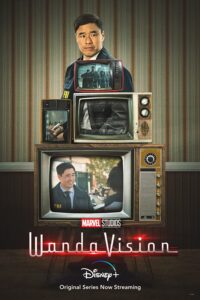

© Disney

I’m sure one of the reasons WV has the chance to experiment with its storytelling style is the fact that Marvel has cemented itself as one of the biggest moneymakers in contemporary entertainment and regardless of what they end up presenting to the viewers, it is guaranteed that they’ll make even more money from whatever they put out. It should, therefore, make for a fortunate chance to subvert and revamp the formula they’ve been using so far.

Alas, I wish.

The cast

The biggest reason WandaVision manages to keep the audience watching despite its unexpected experimentation with tradition that might deter less adventurous viewers is definitely its cast.

The two biggest players, Elizabeth Olsen and Paul Bettany prove themselves once again for the great actors they are. For the most part, the show is very busy making clear that the characters are as familiar with their environment as they are trapped by it, which gives the two the challenge of having to be entirely integrated with the role they and the characters themselves have been given while at the same time having to display how completely out of place they are. It’s not an easy balance to achieve, but they do it wonderfully.

© Disney

Concurrently, the secondary cast – comprised almost entirely of characters that are already well-loved but not protagonists in their own franchises, played by Kat Dennings as Thor‘s Darcy Lewis, Randall Park as AntMan‘s Jimmy Woo, Teyonah Parris as Captain Marvel‘s Monica Rambeau (now all grown up) – does a splendid job of not only rooting this wacky story in the greater Marvel universe but also being just extremely lovable, which is kind of a given. It is an unexpected but entirely welcome team-up that fans will definitely want to see more of in the future.

The Marvel prison

If WandaVision is such a demonstration of original subversion of tropes, lovable characters, and interesting plots, what is the problem then?

© Disney

Despite its impressive display of emotional storytelling of a story that deals with the grief of loss and trauma in such an unexpectedly sincere and profound way, the show climaxes, like pretty much all recent Marvel productions tend to do, with a big CGI battle that the audience most likely already knows the outcome of.

While most of the story is centred around the emotions of the characters and avoids being in the audience’s face about it like it hasn’t quite been able to do so far with its theatre releases, that subtlety and emotional dept is completely thrown away the moment the show reinforces the idea that the only reason viewers watch any Marvel production at all is the big – huge, always huger! – artificial fights. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t exactly associate the Marvel name with introspective, indie-movie development of characters and stories, but it’s also true that fights should have a function in the tale they’re trying to enrich. It’s something that Marvel has been obviously misunderstanding when it makes the final big, bright explosion the only possible peak for any given conflict.

The rest of Marvel TV

That said, why make the comparison to the shows hosted on other platforms at all, especially the Netflix ones?

© Disney

I’ll be the first to admit that I haven’t seen all the Marvel TV shows that have come out to date. While I still keep a close eye on the theatre releases that keep coming out today – not particularly enthusiastically anymore, it bears saying -, I haven’t been able to get into the television productions as much as Marvel would surely like any one of their viewers to do.

I watched Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. for a good part of its run as I did for Agent Carter; I tried my hand at Cloak & Dagger without much success while Runaways I got easily attached to; I wasn’t particularly heartbroken about Inhumans‘ cancellation and didn’t even know about Helstrom‘s existence before this article; even though I watched or tried to watch most of the Netflix shows, only Jessica Jones and Luke Cage struck a particular chord with me while I couldn’t go beyond just a few episodes of Daredevil and found Iron Fist to be remarkably unimpressive especially after JJ and LC and up the to point where Coleen started taking on a bigger role in it (after which it was cancelled) but was still pretty disappointed to find out that would be the extent of Netflix‘s involvement in the Marvel adaptations (Defenders wasn’t as good as I’d hoped and while Punisher was extremely interesting, I’m not the biggest fan of gratuitous violence).

The reason why I’m particularly fixated on the Netflix shows in contrast with the current schedule of Disney+ shows, and specifically WandaVision, is because both took a much closer look at the inner lives of the characters they revolved around, but while Netflix managed to subtly and successfully show that the story could reach a climax and a climactic battle without it taking centre stage over the characters that are supposed to drive the story, WandaVision followed that annoying tendency of dropping most of its emotional weight for a few not-that-cheap shots of artificial VFX that Marvel keeps thinking is everything the audience is waiting for in their productions.

© Disney

WandaVision could have concluded its brief but significant run by sustaining and enlarging its emotional potential, especially when linked to such an interesting character as Wanda Maximoff, but elected to interrupt the emotional narrative it had developed in smart and creatively deconstructive ways instead and never quite managed to pick that emotionally weighty thread back up to a satisfying, but still curiosity-inducing end.

By the time the last episode of what had been an unexpected and medium-explorative show came to an end, all of the impact that the knowledgeable narrative structure had had on me up to that point simply evaporated and I was actually relieved that would be the end of my enduring the obligatory but unnecessarily long and prominent big CGI fights, at least for this run.

Final thoughts

All in all, for the most part, WandaVision does approach the genre it is confined to in impressive and creative ways and it remains a watchable show that I would recommend to someone looking for different storytelling to a pretty standard Marvel story, with the small caveat that it does not entirely deliver on the potential it builds from the first episode.

In the end, all Marvel shows and movies exist in the interest of perpetuating a saga that is simply making too much money to come to any kind of satisfying and consequential ending anytime soon and will definitely end up – if it hasn’t already – becoming a franchise that people get exhausted by. With that consideration, it would be a lot more refreshing to see the power and bullet-proof name it has be put to the service of true subversion and originality without chickening out at the last moment.

We have to be realistic, though, that won’t be happening anytime soon.

Analisi incredibilmente attenta, complimenti! Studiata e minuziosa da ogni punto di vista.

Ti ringrazio moltissimo!!! ♥ ♥